Prison Reform : Reducing Pre-trial Detention

A. Strengthening pre-trial safeguards

B. Monitoring court production

C. Monitoring Undertrial Review Committees

D. Ensuring effective access to legal aid

Undertrial prisoners constitute a significant majority of the prison population (67.6%) in India. In 2016 as many as 3927 undertrials had spent more than 5 years in prison and awaited completion of their trial. These high numbers also result in high occupancy rates (113.7%), which in turn are linked to substandard living conditions in prisons.

Persons who are confined in prisons as undertrials are presumed to be innocent in the eyes of the law. The consequences of pre-trial detention are grave. Defendants presumed innocent are subjected to the psychological and physical deprivations of jail life, usually under more onerous conditions than are imposed on convicted defendants. The jailed defendant loses his job if he has one and is prevented from contributing to the preparation of his defence. Equally important, the burden of his detention frequently falls heavily on the innocent members of his family.

From time to time the government has introduced plans to reduce pretrial detention rates, yet no radical change has been perceived. The Supreme Court too has periodically issued directions for the release of undertrials and liberal use of bail provisions, but this has not led to any change in the high percentage of undertrials lodged in prison.

We at CHRI believe that strengthening pretrial safeguards, monitoring court practices, periodic review of prisoners’ cases and access to effective legal representation are three important aspects linked to reducing pre-trial detention rates in India.

A. STRENGTHENING PRE-TRIAL SAFEGUARDS

In 2010 the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 was amended and Sections 41A, 41B, 41C and 41D introduced to place checks on arbitrary and unnecessary arrests as well as prevent abuse of process and opportunities to torture by the police. Section 41A mandates issuance of notice by police before arrest in offences punishable with less than 7 years imprisonment; section 41B mandates the police to submit arrest memos for scrutiny by magistrates at production; section 41C CrPC requires police control rooms to be established in every district and display of names and addresses of persons arrested and the name and designation of the arresting police officers every are to be displayed on their notice boards; and section provides an arrested person a statutory right to a lawyer at the time of interrogation after arrest, though not throughout. These provisions if implemented in true spirit provide robust safeguards against unnecessary and arbitrary arrests, which also afford checks against the possibility of torture, illegal confessions and unncessary pretrial detention.

We have conducted studies on Section 41B (memo of arrest) and Section 41C (transparency about arrests), and has prepared pamphlets on possible models of establishing legal aid clinics in police stations to ensure compliance of Section 41D and access to legal representation to those unable to afford such representation.

Our police team has conducted a study on Section 41B CrPC -- ‘Arrest Memos: A Study on Requirements and Compliance in Rajasthan and West Bengal’(2016) looks at police compliance with the essential requirements of Section 41B(b) and judicial magistrates’ scrutiny of arrest memos when the arrested person is first produced in court. It indicates that there are no standardised formats for arrest memos. This directly affects the recording of content in arrest memos, witnesses are usually ‘friends of the police’ or unknown entities when the law is very clear that the witnesses have to be either a relative of the arrested person or a resident of the locality where the arrest is made. The magistrate’s examination of documents is cursory and little effort is made to verify the details of the arrest. Lawyers too do not press magistrates for compliance. In fact, compliance, even on paper is lacking.

Our study on Section 41C CrPC -- ‘Transparency of Information about Arrests and Detentions’ (2016) highlighted that formats and guidance have not been issued in most states and where they have been issued they are poorly implemented. It further provides evidence that budgets are not allocated for channelising information flows from the police stations to the headquarters and for creating publicly accessible databases of people arrested. Supervisory cadres have done little to monitor compliance with these statutory requirements and there is little uniformity of practice across the handful of states that actually comply with these requirements.

On compliance with Section 41D CrPC we had conducted an e-consultation on ‘Improving Legal Aid’ conducted in 2016, responses of which (pertaining to section 41D) have been collated into a document – Legal Aid Clinics in Police Stations: Recommendations. It also contains a recommendatory model by CHRI for an effective legal aid clinic to be setup in a police station. Additionally, we have also prepared a booklet which gives guidance on setup of legal services clinics in police stations – Legal Aid at Police Stations.

B MONITORING COURT PRODUCTION

A duty rests on the criminal justice system and particularly the magistrate in the trial courts to safeguard the life and liberty of the accused. They are bound to ascertain the necessity of arrest, length of custody and treatment during custody as laid down in the law so that no individual is held against the law of the land, or detained beyond a period that is absolutely required. However, the common malpractices such as unnecessary arrest, delay in first production of the accused before the magistrate, lack of physical production of accused due to shortage of police escorts, mechanical remand, delays in investigation, filing of chargesheet and framing of charges compromise the rights of the individual to have timely and equal access to the law. As a result, the accused is forced to spend longer period in detention than necessary.

The presence of an accused during his trial is a fair trial right guaranteed under various human rights instruments as well as under the constitutional and statutory framework in India. The right to be tried in one’s presence is implicit in the right to adequate defense. The absence of the accused vitiates the entire proceeding whether the proceeding is merely a continuation of remand or a substantive hearing. Similarly, an accused has to be physically produced before the court for it to decide whether the accused needs to be further remanded to custody. Every single day of detention must be justified in the eyes of law. Physical presence of accused in court gives them the opportunity to challenge the status of detention.

In such a context, we have undertaken monitoring of court production in Rajasthan and West Bengal, to ascertain whether procedural safeguards for life and liberty are indeed being implemented by the upholders of the law. We have conducted visits to courts to observe remand practices and physical production of the accused person. We have also undertaken sessions with judicial officers at the West Bengal State Judicial Academy and the National Judicial Academy, Bhopal that have stressed upon the role of magistrates at production.

In 2008, the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2008 amended Section 167 (2) (b) of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (CrPC) and introduced electronic video-linkage as an alternative method for production of an accused in court. Even though video conferencing enables the Magistrate to be face to face with the electronically transmitted image of the accused, without appropriate safeguards in place, the benefits of using video conferencing over physical production are trumped by violations of an accused’s right to fair trial. In view of this, and with the increasing use of video conferencing for conducting productions and now trials as well, we have prepared a document -- Draft Guidelines for Video Conferencing between Courts and Remote Sites and have also undertaken sessions on safeguards to video conferencing at trainings conducted by the Bureau of Police Research and Development for judicial, police, prison officers and prosecutors from eastern, southern, western regions.

- Handbook on Role of Magistrate at Production (2019) – UPCOMING

- Draft Guidelines for Video Conferencing between Courts and Remote Sites (2018)

- The Missing Guard: A Study on Rajasthan’s Court Production System (2014)

- Court Watch – WB (2013)

C. MONITORING UNDER TRIAL REVIEW COMMITTEES

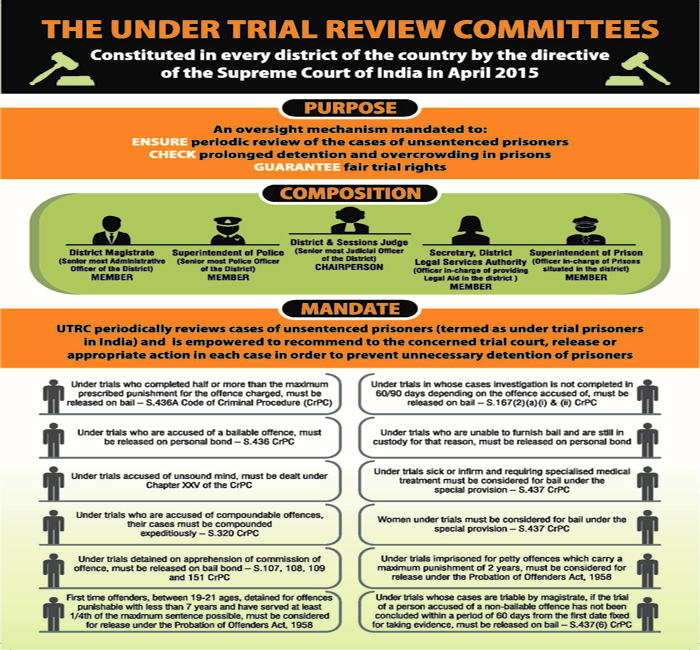

Undertrial Review Committees are an oversight mechanism that is headed by a judicial officer and find representation from the district administration, police, legal aid and prison departments. They are mandated to periodically conduct reviews of cases of undertrials eligible under the categories set out under NALSA’s Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Under Trial Review Committees (UTRCs), prepared as directives of the Supreme Court on India in the In Re-Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons case [WP(C) 406/2013]. These include persons who are eligible to be released on statutory bail, have been granted bail but are unable to furnish sureties, are charged under compoundable offences, are mentally ill, sick or infirm, have been charged with petty offences etc. It also seeks to ensure implementation of Section 436A CrPC which proscribes the detention of undertrials beyond the maximum term of sentence. It also provides an undertrial the right to apply for bail once s/he has served one half of the maximum term of sentence s/he would have served had s/he been convicted.

The concept of undertrial review committees is not new; they have been under discussion since April 1979 when a conference of Chief Secretaries, for the first time, recommended the constitution of district and state level review committees. The All India Jail Reforms Committee of 1980-83, popularly known as the Mulla Committee, had also recommended a regular, effective review mechanism at the district level and the state level. In 2013, the Home Minister too sent a letter to all state governments to set up state-level multi-disciplinary committees to review undertrial incarceration. However, it was only in 2015, in pursuance of a directive of the Supreme Court in the In Re-Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons case that these committees have been mandated to be setup across all districts.

We have been monitoring the setup and functioning of UTRCs. Our national report ‘Circle of Justice: A National Report on Undertrial Review Committees’ (2016) examined the functioning of the UTRCs in India and highlighted that only 40% of the committee meetings complied with the mandate set out by the Supreme Court. We have also conducted studies in West Bengal (2015) and have been monitoring the functioning of Periodic Review Committees (Avadhik Samiksha Samiti), which have been functional in Rajasthan since 1979, through our watch reports (2011, 2013, 2015 and 2018).

We have also prepared an analytical tool -- Evaluation of Prisoner Information & Cases (EPIC). EPIC is a simple analytical tool which assists in computing the eligibility of under-trial prisoners’ u/s 167/436/436A CrPC, evaluating whether cases fall under petty offences, are eligible under plea bargaining or are compoundable/non compoundable cases. Its use is simple, and results are quick and accurate. EPIC has been developed as a set of analytical instructions which evaluate the period of detention for each under-trial prisoner. However, while EPIC has been developed on an excel sheet, and can be used by individuals, it can also be integrated in the prison management software. Such an integration can make identification of prisoners who are eligible for release on bail or otherwise automated, thus providing a check on unnecessary and prolonged detention. We have prepared a specification document to facilitate its integration.

Relevant Publications

- Flyer on Under Trial Review Committees in India (2018)

- Guiding Note: Revised Mandate For Under Trial Review Committees & Suggested Action

- Circle of Justice: A National Report on Undertrial Review Committees (2016)

- Undertrials: A Long Wait to Justice (2011, 2013, 2015, 2018)

- Under Trial Review Committees: Setup and Functioning in WB (2015)

- Under Trial Review Mechanisms in WB (2013)

- EPIC- Evaluation of Prisoner Information and Cases

- EPIC – Specification Document for Integration into Prison Management Systems